Making Things is Hard #4: Lee Wilkof

“I’ve said this, and it’s a little bit of an exaggeration, but the dressing room is more important than what happens on the stage.”

Hey! Hope you’re having a lovely Thursday. And, if you’re on the East Coast like me, experiencing this heat wave, I hope you’re finding lots of shade/AC/very powerful fans.

Before I get into this week’s interview, I wanted to formally invite you to come see me perform in a concert later this month along with the subject of my VERY FIRST INTERVIEW on here. Yes, that’s right, I’m talking about the incomparable Joe Iconis.

He’s got a run of Iconis & Family shows coming up at Feinstein’s/54 Below that I highly recommend you attend. Joe and his songs are incredible, as is the band, as are all the performers, and it’s a true feel-good time. The run is from Tuesday, July 30th through Saturday, August 3rd, all shows at 7 pm. I’ll only be doing the shows on Tuesday, 7/30, Friday, 8/2, and Saturday, 8/3, so try to come to those! Tickets here.

Okay. Let’s get down to bidness.

Today’s interview is with Lee Wilkof, a brilliant actor, writer, director, and person. He’s done so much amazing work, including creating the role of Seymour in the original Off-Broadway production of Little Shop of Horrors and the role of Samuel Byck in the original Off-Broadway production of Assassins. He was nominated for a Tony Award in 2000 for his performance in Kiss Me Kate, and has been in many other Broadway shows including Waitress, The Odd Couple, and She Loves Me. He’s also had a great career in TV and film, including appearances in The Marvelous. Mrs. Maisel, The Grey Zone, School of Rock, and Ally McBeal.

And, on top of all that, he directed and co-wrote the charming and funny 2016 film No Pay, Nudity, starring Gabriel Byrne, Frances Conroy, and Nathan Lane. He’s working on a new short film now entitled Teenage Waistband, along with co-writing a fantastic musical with Rob Morrison tentatively titled Brotherly Love, inspired by the Ward brothers murder case from 1990.

But, more important than all of this, he’s been a mentor and friend to me since I met him twenty years ago when I was an apprentice at Williamstown Theater. When I moved to New York City after that summer, Lee would take me to lunch and let me pick his brain about acting and was generally such a funny, warm mensch—I will be forever grateful. Over the past two years, I’ve been honored to work with him on the musical he’s co-writing as a consultant—reading drafts and giving notes—and it’s been such a delight to collaborate with him.

Lee and I talked over Facetime, literally the day after he became a grandfather! I’ve condensed and edited our conversation for your enjoyment.

Hi, Lee. So you’ve had this illustrious career—acting, writing, directing. What have been your favorite moments or favorite type of moments?

For me, the favorite moments have always been about the people that I work with. And some experiences—there’s one show in particular that everybody just assumes is my favorite experience because it was the one with the most… Well, it’s Little Shop. Let’s just put it out there. Little Shop of Horrors. And it was a phenomenal experience. I met my wife. It changed my career. It gave me some presence, which kept things going for a while. But the personnel…were tricky. And it was not that satisfying.

The shows that have been the most satisfying— I’ll back up a little. When I went to college, I didn’t know what I was gonna do, but I walked into the theater and I found a family. And on every show, a family is created.

But, of course, you want a functional family. I’ve said this, and it’s a little bit of an exaggeration, but the dressing room is more important than what happens on the stage. And it’s not totally true, but that combination of a great show with great personnel is… Like when I did Assassins. Between the brilliance of the piece and then the backstage dressing room, it was just extraordinary. And a show like Socrates [Note: written by Tim Blake Nelson, ran at the Public in 2019]. And those have brought me the greatest fulfillment, and then of course the relationships that have developed. But it’s not always the best show that is the most satisfying. It’s the personnel.

I’m difficult to work with, not because I’m difficult, but because I’m very slow. Very slow. It’s a little ridiculous that I compare myself to Lee J. Cobb, but people wanted him to be fired from Death of a Salesman, and luckily Elia Kazan said, “Let’s just wait, wait, wait.” He was really slow. Because either his process or… With me, I’m a little dense. And my process is slow. I haven’t been, to be perfectly honest, sufficiently trained. But I find my way. Most of the time. So the combination of the piece and the people…

Doing No Pay, Nudity was just glorious because of the people that were involved. And that’s my greatest joy. Having moved upstate and not being around theater people has been the most difficult thing for me. I’m not around my people. Theater people—we’re funnier. We’re creative. Not that the people I know where we’ve moved aren’t decent, kind people. But they ain’t show people.

I love what you’re saying about Little Shop because when I was growing up, and I had stars in my eyes about acting, I always assumed the most successful, famous thing was what was gonna feel the best. But, the longer I’ve been in this business, the more I see that couldn’t be further from the truth. It’s so much about the people, the relationships, the connections. And if that’s not there, you can be working on the best thing, and it’s gonna feel like shit.

The interesting thing about Little Shop was that, no matter where I did it, it was always weirdly fraught. It had weird juju. Something was tricky about it. I don’t need to go into details, but… I have strived in my career to be decent. Not difficult. There’s no reason to be. I’ve seen a lot of people being difficult, but it’s insecurity. And it’s ego. I have a healthy ego, but I’m just not a troublemaker. Except it takes me a long time. It’s gotten difficult for me to remember my lines, I hate to admit it. That’s my own burden.

We’ve got apps for that now, Lee.

Thank god.

I’m really fascinated by you talking about your slow process. In terms of a creative struggle, just that feeling of not keeping up the way you should be. I’m wondering how you’ve made peace with that over a long career.

I’ve made peace with it, but I also am very self-conscious about it. I worry that people lose patience with me. The last show I did— Well, I was struggling with lines, and the director said… How did he put it? “Woodshed it!” As in: go into a woodshed and don’t come out till you learn your f*cking lines. He was frustrated with me.

I guess it’s just the technique I’ve developed. It’s maybe working from the ass forward. Rather than forward to the ass, so to speak. But it’s my technique. It’s probably frustrating for people. But ultimately, I’m there on game day. I’m there. Some people want you to be there the third day [of rehearsals]. I’m not capable of it. I have a technique. It’s probably not particularly conventional, but it seems to work.

And the business has changed—everything has become contracted. You used to have, let’s say, five weeks of rehearsal. Now you’re lucky if you get three. So that’s something that I deal with.

Can you think of a process or show you did where you weren’t getting where you needed to with the role fast enough, and it was starting to really stress you out, and then you got there?

Yes. It was working for a director who was notorious for always firing somebody. It was Assassins. It’s head and shoulders above anything I’ve ever done. The role. Sondheim. The personnel. But it was Jerry Zaks [the director], and I was kind of aware of his reputation. ‘Cause I had worked with him actually some years before. I did The Front Page at Lincoln Center, then we moved to LA.

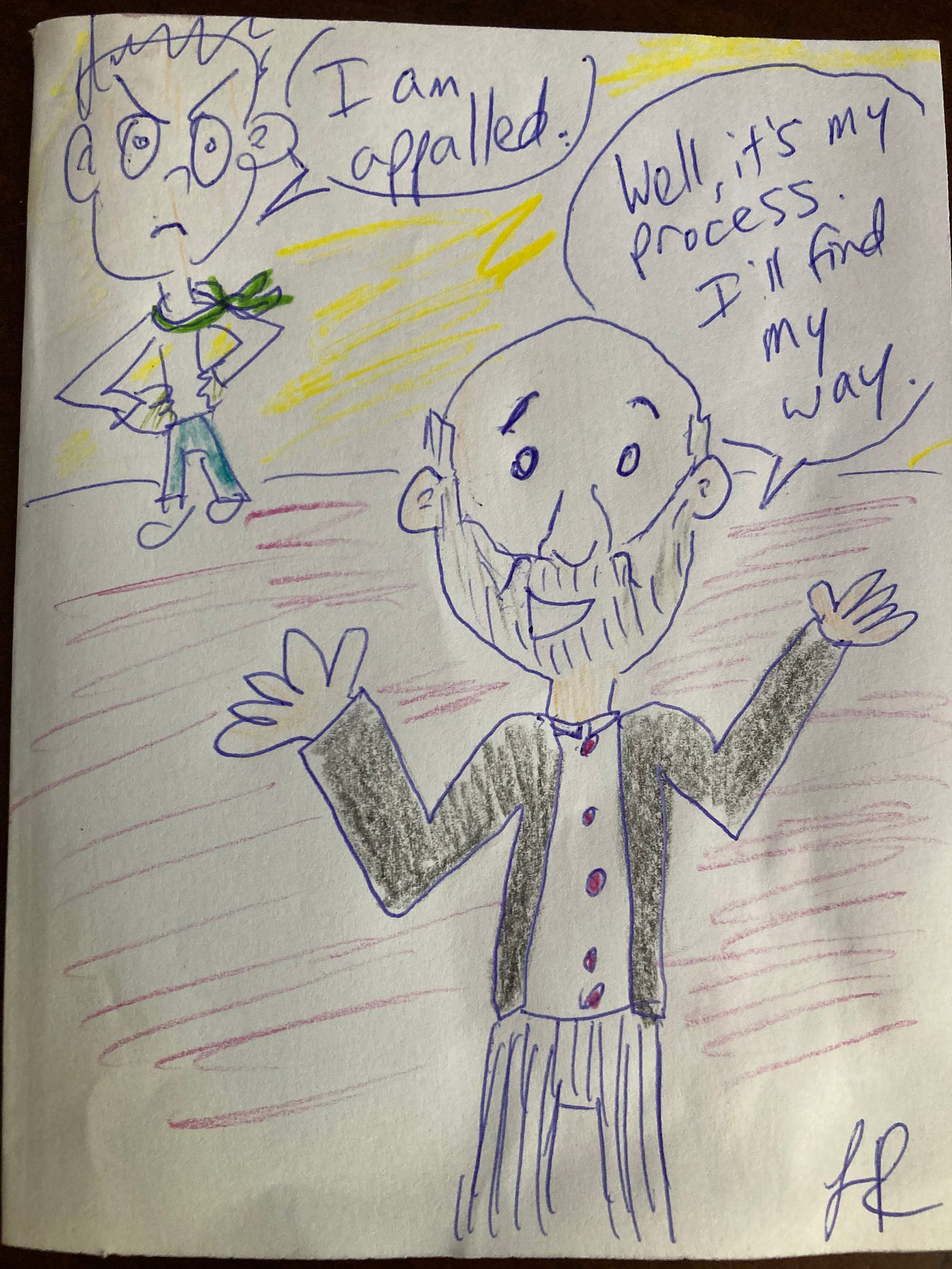

So [during Assassins] I lived in complete fear, and [Jerry Zaks] left me alone to find it on my own. With me, it’s just doing some sort of back-ass process where eventually the dreck is moved to the side, and it eventually clicks. I make all sorts of bad choices, and then I kind of distill it into hopefully the right place. He just left me alone, and I found it. But I remember there was an actor in it— He was appalled at my process. Appalled at what I was doing.

I was the only actor in the show—and these were the highest level people—I got a Drama Desk nomination, and no one else did, and it was shocking to a few people because they witnessed my kind of grotesque process that eventually… I found my way. Because I believe ultimately it’s within me, but it’s just, like… It’s a slog to find it.

I didn’t go to grad school. I took acting class when I got to New York with Austin Pendleton, and I was probably not paying attention. And then 35 years later, I took it again, and I did. I wish I paid attention that first time because he really… I haven’t worked much since I had this second class with him about fifteen years ago, but it’s been really…I’ve kind of found my way. I haven’t really worked on a play since before covid. So I’m anxious to see if I’ve still got it.

Oh, you do. I know you do. Speaking of the Drama Desk nomination, you’ve also been nominated for a Tony. Do you remember how your ego related to those nominations? What were the feelings then? Did it go to your head?

Well. I’ve been nominated three times for Drama Desks. The first time I didn’t even realize what it was. And I went to the ceremony, and I found it more interesting than anything. I was in shock about that one. I was in this silly revue, and I was very lucky that my pieces in it scored. I got an amazing review in The NY Times, and Norman Lear came to see it. Flew me out to LA. I had always imagined that my career would be as a sitcom guy. The problem was my process. On a sitcom, if you don’t get the laughs by day two, you’re in trouble.

Then the second time was for Assassins. And my ego was a little elevated. I mean, I was in a cast with Victor Garber, Debbie Monk, Terry Mann, Annie Golden, and I’m the schmendrick that got the Drama Desk nomination? But the part was so great. And I must have been somewhat effective. It was an ensemble, but I just did monologues. They were all doing scenes and stuff, I just sat onstage and did three monologues. So it was a unique part in it.

And the last Drama Desk nomination was when I was also nominated for a Tony for Kiss Me Kate. That was just… First of all, the role is a gift. If you don’t get a Tony nomination, you fucked up. It’s Laurel and Hardy. Laurel can’t work without Hardy, and Hardy don’t work without Laurel. And I had this guy I did it with Michael Mulheren, we just were like—he’s the big football player, and I was the little—I wasn’t shrimpy, but I was pretty skinny then. And I had a director, Michael Blakemore, who just passed away—may he rest in peace—he just… That one I didn’t lag behind because he just gave me line readings, he told me what to do, I just did what he told me to do. And we had a brilliant choreographer, and we had the eleven o’clock number. I didn’t know the show. They wouldn’t give me a script, I just saw sides [Note: sides are the excerpts of the script provided to audition with]. And then I got cast and somebody said, “You have absolutely no idea what you just scored.” I was very lucky to get cast. Very lucky.

Looking back at your career, what would you tell young you, and young anybody going into a career in the arts and theater, that you didn’t know then?

This is not like great wisdom. But there are people I know who have been very frustrated at the way they get stuck in musicals. They want to do more. I used to insist—and I don’t insist much from people, I fear almost everyone—when I had my agent, I would say, “I can sing”—although I can’t sing very well any more since my throat cancer—but then, after having done a musical, I’d say, “Let’s go for a non-musical.” And it was important to me because I wanted to work in all of it. I wanted to work in film, TV, straight plays, musicals. I was lucky I could sing, I was lucky I was a character guy. So that was really critical to me. And I was actually smart enough to insist on it. And they listened!

So if you want to do something, then you gotta let people know. My career, it’s been important for me to try to do it all. And directing the film, it wasn’t something when I started my career: “I’m gonna direct a film!” It just happened. And now I’m doing another one, a short.

I’m at the end of my career, and I’m not certainly not working as much as I want to. I’d hoped to have [more of] a career in film. I think doing Little Shop of Horrors is certainly important to my career—as I mentioned I met my wife, I wouldn’t have my daughter and my granddaughter, and I wouldn’t have been with Connie for 42 years. I played a nerd, and it got me recognition, but it also pigeon-holed me. There are projects that I wish I could have been involved in and I wasn’t and that’s frustrating, but I know many other actors who feel the exact same way.

But I’m really lucky. And I miss doing it because I love it. It’s important to me to be stimulated. I love the process, even if I don’t know what I’m doing. Getting people to laugh. Laughs are pretty important these days.

Huge thanks to Lee! I loved talking with him about his career. And hopefully you did too. Thanks as always for reading. Have a super day and weekend, and don’t be afraid to be slow!

I love this series. :)

who is this dope?